Mitsouko

For Robert Lyons – June 2006 (about „Intimate Enemy, Images and Voices of the Rwandan Genocide“) - a never send letter.

„When you first presented some of your pictures you asked us the question, if we could identify victims and perpetrators. I thought that an odd question and I didn‘t get why you asking it. (What I saw in your pictures was only sadness.)

When I read your PHOTOGRAPHER‘S NOTES (1) I understand why it was important for you to ask this question and I understood why it was impossible for me to understand: I am german; more or less the first generation after the holocaust and the war. I grew up with the survivors and the others. There are my family.

When I was 14 on vacation in a youthcamp in France, I got very sick, so I had to see a doctor. The doctor wanted to be helpful and asked a man from the village to translate.

When I started to speak the man just stared at me, unable to move, unable to speak. He was as old as my grandparents.

It was the first time I had to face, that to be german means you have a history of violence you can‘t ignore: that was the moment I not only know but felt what collective guilt meant.

The next time I saw your pictures was at Petras apartment and then one sentence was constantly repeating itself in my mind: „the dignity of man is untouchable“. (2) Out of my own experience with violence, I know it is not. It is touchable.

What violence does and what I saw in your pictures that very moment was the sadness over that loss. You might be able to get back your dignity, but you will never be untouched again. It will change your perspective on this world forever.

The following nights I was haunted by a dream: I was in a farmhouse. It was at night and in every room there was a sort of intimate light, which created a warm atmosphere. I wasn‘t alone; a group of faceless people accompanied me and we were busy killing other people in a completly careless indifferent manner. The floor was full of dead people, but there was no blood at all. Not even on me.

In a certain moment I said we should stop that, like you say you should do some sport, and we agreed to leave the house. It happend to be in an industrial area with floodlight and fences. But we climbed over, coming to a street of new buildings perfectly equal. We just walked into a building, into an apartment and killed further in the same manner.

What I know about dreams is you are always everybody: victim and perpetrator at the same time.

A long time ago, I got that the process of violence doesn‘t end in the moment you survived it. It leaves traces through generations. But what I didn‘t realize up to a year ago was that as long as you see yourself only as a victim you neither be able to change anything nor you are able to see your own part in this process. I transform violence through fear into another form of violence and as long as I am not able to control my fear, I will continue the process. The involment of my family in the holocaust and the World War II was discussed, meaning I was allowed to asked questions about my grandparents and their position, but what was never had been a subject was the emotional and psychological impact the experienced violence had on the survivors.“

The reason I never send this letter was, that instead of a book review I wrote down my motivations for „Mitsouko“. Reading them now in April 2007 I can say, there are as true as there were in June 2006: thinking about violence means for me to look at its changing forms in a process of continuity, the traces of violence in the history of my country, the history of my family, my history. The feeling of fear seems to be dominant not only for my reality construction but in a more general way . So the question I like to ask is, what do we mean when we say „idyll“ ?

(1)“But by closing the space between ourselves and the „other“, we can perhaps begin to ask more critical questions, to change fixed patterns of behavior, to arrest the impulse that reduces individual strangers to mere savages and, in so doing, conveniently absolves us of complicity in or responsibility for their actions.“ (Intimate Enemy, Images and Voices of the Rwandan Genocide, ZONE BOOKS, New York 2006, S.34/S.35, Photographer‘s Notes/ Robert Lyons)

(2) Grundgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Artikel 1, Absatz 1: “Die Würde des Menschen ist unantastbar. Sie zu achten und zu schützen ist Verpflichtung aller staatlichen Gewalt.“

(Constitution of the Federal Republik of Germany, 1st article, 1st paragraph: „The dignity of man is untouchable. To respect and protect it is the duty of all the state‘s powers.“)

Andrea Brehme , April 2007

group exhibition „ABSCHLUSS“

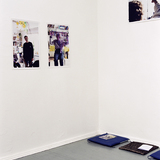

Mitsouko

2006 – 2007/ 2007

A work about fear.

form/format: c-print 23,6 x 19,7 inches (vertical formats) / 23,6 x 27,5 inches (horizontal formats), aluminium/aluminum

negative – middle format 6/7

presentation: „ABSCHLUSS“ Projektraum 1, Kunstraum Kreuzberg/ Bethanien, Mariannenplatz 2, D-10997 Berlin, Germany

exhibition: April 21th 2007 – May 13th 2007 / / group exhibition